Why Apologies Are Overrated: “I am so sorry for the harm I have caused”

- 16

- Feb

- 2015

Rather than seeking forgiveness, how about making things right instead?

Rather than seeking forgiveness, how about making things right instead?

It has become popular these days to forgive. Or at the very least, to ask for forgiveness. Whether you are Charlie Sheen, Mel Gibson, or Dior’s Creative Director John Galliano, it seems you can say the most offensive things then have your media coach make your public image clean again by orchestrating a contrite plea for forgiveness. Politicians who dally in their mistresses’ beds and whole governments whose predecessors committed cultural genocide say “I’m sorry” and seek the forgiveness of those they’ve harmed. Forgiveness is even popular in couples counselling where the tendency now is to invite a cheating spouse to tell their partner exactly what they did and, you guessed it, ask them to understand.

It has become the fashion to expect the innocent to show beneficence to those whose transgressions have caused harm with apologies. Am I the only one who is becoming cynical?

I was thinking about this while in Cambodia meeting Youk Chang, Director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, who is tasked with gathering evidence of the grisly crimes against humanity committed by the Khmer Rouge (typically remembered in the west as The Killing Fields). Chang has rooms full of documentation, testimonies and photographs of those were tortured and imprisoned.

I was surprised when he told me he does not believe in forgiveness. The process of truth and reconciliation, he says, is a strictly western, Christian idea. In Christian terms, he says, life is lived in a straight line, from birth to death to salvation. One can be absolved of their sins, find heaven, and of course, forgiveness. As a Buddhist, Chang prefers to think about life as a cycle. We have to actively undo what we have done wrong (or else we will reincarnate as a cockroach!). I’m no Buddhist scholar, but the idea that Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, and the forgiveness that they promote (think Nelson Mandela and South Africa) is a naïve culturally-embedded idea struck me as shockingly true.

Forgiveness is a lofty ideal. I would prefer, like Chang, that we lived in a world that promoted accountability instead. I see this all the time in my work with delinquents. They are encouraged strongly by the courts to write letters of regret to their victims. Then they do a hundred community service hours at the local YMCA, as if somehow mopping floors there is atonement for the car they stole and burned, the family they frightened, and the money they stole from others. Let me say this plainly: I havenever in my career as a therapist who specializes in working with these kids met a delinquent who felt their community service hours made them a better person or was in any way helping to make things better for their victim. It’s a sad myth we like to tell ourselves, another part of the illusion of forgiveness and atonement.

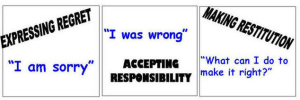

What, then, does work? Whether you are a genocidal dictator, a parent who neglects his kid, a teenager who steals, or a movie star, true accountability is achieved through right action. When we make a mistake, we need to do something for the ones we’ve harmed to make things right. There is the proverb of the soldier who slays his enemy but rather than forgiveness, is told by his Priest he must raise his enemy’s child as his own. That to me is active forgiveness.

If my government wants to seek forgiveness for its history of mistreatment of Chinese immigrants, Aboriginal peoples and other minorities, I say do more than apologize. Promote tolerance through your immigration policies, address racism in the school curriculum, and give those we’ve harmed the means for a decent living.

If Charlie Sheen, Mel Gibson, or John Galliano want forgiveness for their rants, then let them spend some time caring for those who suffered during the Holocaust. Let’s see them do something to preserve our collective memory of atrocities and ensure such things never happen again. At the very least, they could spend an afternoon with Youk Chang, or others like him who do work like his that documents genocides.

If life is a cycle then we are accountable for what we’ve done. Whether one believes in reincarnation or not (I don’t) one can still do in this lifetime what must be done to put one’s actions right. But forgiveness, that is something I’ll guard jealously. Show me, rather than tell me, you have changed.

Receive My Newsletter

Categories

- Abuse

- Anxiety & Panic

- Comics

- Dating

- Depression

- Eating Disorders

- Emotional Issues

- Family Issues

- Happiness

- Individual Concerns

- Marriage / Relationships

- Mental Illness

- Parenting

- Personality

- Positive Suggestions

- Stress

- Suicide

- Teenagers